Traceability in Agribusiness Value Chain

Various drivers are creating pressure to increase the traceability of and information about the food we eat.

First, concerns over food safety have been fanned by events like the BSE crisis, melamine in Chinese milk, E coli in German beansprouts and, most recently, horsemeat contamination of beef in Europe.These have been behind the formation of bodies like the European Food Safety Authority, and also provide opportunities for Western companies to apply their knowledge and expertise in emerging markets.This is reinforced by increasing interest in the nutritional and health properties of the food we eat.

Second, the rapid rise of GM crops, which have achieved significant penetration in some countries and crops, has resulted in labeling requirements in around 40 countries, particularly in Europe, but also in China and Russia. As the crops where GM has so far achieved significant penetration are commodity crops, this creates new requirements for identity preservation, and can be a barrier to trade. Having said that, other countries, notably the US, are strongly opposed to labeling for GM crops.The US position was reaffirmed by the rejection of GM labeling in a vote in California in November 2012.

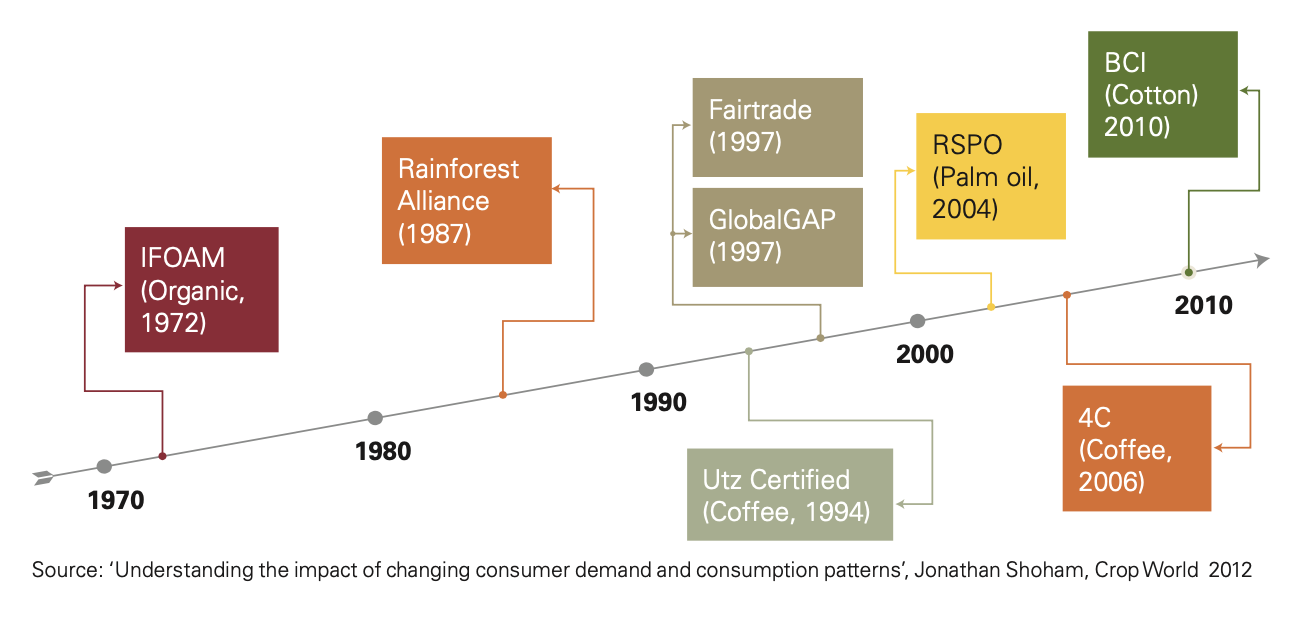

Third, consumers want to know not just about the content and safety of their food, but also how it is produced and what the environmental and social impacts are. As people ascend the economic ladder their requirements in this respect become ever more demanding.This has resulted in the introduction of voluntary certification schemes such as ‘Fairtrade’ and ‘The Rainforest Alliance’. Increasingly food companies are adopting these schemes and making commitments to improve the sustainability of their sourcing and operations.There has been a proliferation of such schemes over recent years, as well as a diversity of approaches. Fig. 10 gives a timeline for some of the major schemes introduced over the last 40 years.The proliferation and variety of schemes reflects the environmental and social impact of agriculture which is greater (and more complex) than that of any other sector. Concern over this aspect of agriculture is also reflected in the widespread adoption of the concept of ‘Sustainable Crop Production Intensification’ an approach designed to balance the need to increase productivity with the need to minimize negative environmental impacts.This is promoted by the FAO among others and widely supported throughout the private and public sectors.

Accommodation of the above pressures is facilitated by advances in technology and the supply chain.The rapid increase in penetration by large retailers brings with it more sophisticated and efficient supply chains which permit ever improved traceability and information provision. At the same time new lifecycle analysis tools and methodologies are being developed which improve the accuracy and detail of information on the environmental and social impacts for food production. An example of this can be found in the development of carbon labeling.The Sustainability Consortium in the US is playing a leading role in this area.Table 4 looks at drivers of and responses to the ever increasing requirements for scrutiny along the agri-food chain.

Despite these developments, penetration of voluntary standards is still very

low. Organic production has only 1-2 percent global market penetration and is far better established in Europe than anywhere else. Other more recent certification schemes such as Fairtrade and the Rainforest Alliance account for well under

1 percent of global consumption, although still growing fast. More significant in terms of impact are some of the mandatory directives and policies which have been introduced, particularly in Europe, where for example, the nitrogen directive has led to significant reductions on the amount of fertilizer overuse and pollution, and farmer subsidies are being made increasingly conditional upon environmental compliance.

There are choices which are common to different stages in the value chain:

‘Make or buy’:should companies adopt existing standards and certification schemes or develop their own. Most companies elect for the former although some of the larger ones also do their own thing.

If they buy into existing schemes which should they choose? To some extent the choice will depend upon their business profile, product range and environmental impact, but there will still be considerable discretion within these constraints.

What reporting format should they follow: for example having a separate corporate social responsibility report or integrating it into the annual report? Having said that, GRI8 has become a de facto standard.

Such considerations are important as they can affect the attractiveness of a company to investors, potential employees, customers and as a potential M&A target. Moreover the rapidly evolving nature and complexity of this area offers opportunities for differentiation and distinctive positioning.

The sustainability dimension is not only a matter of managing reputational threat but can also lead to identification of new business opportunities and lead to improvements in business efficiency. The process of lifecycle analysis can in itself lead to a better understanding of product and business processes.